- Home

- Expressions by Montaigne

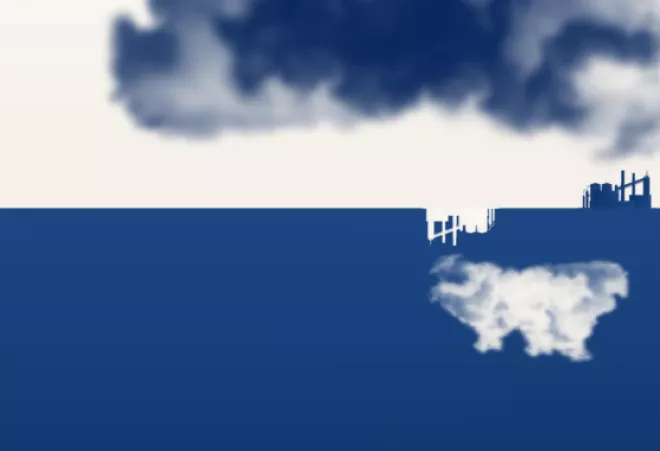

- The Fall of Kabul and the Weight of Western Defeat

Looking at the images coming out of Kabul, it is easy to draw a parallel between what has just happened in Afghanistan and the fall of Saigon in 1975. The same helicopters are hovering over American embassies, the same scenes of chaos are unfolding, former local friends are facing the same betrayal…

For those who support President Biden's decision to withdraw, the comparison is not as shameful as it might seem. In both cases, it was a matter of putting an end to a commitment that has already lasted too long, for which no positive outcome was possible, and above all, which no longer garnered public support. Today in America, "ending forever wars" is one of the few points which Republicans and Democrats agree on.

Does the United States feel humiliated? No doubt it does, but of course, that too shall pass. International politics do not rely on emotion. In a few weeks, perhaps less, media and public attention will have shifted to other news.

A more serious issue is whether the United States’ credibility on the world stage has been seriously damaged. Here again, the comparison with Saigon is ambiguous: fifteen years after Saigon, the United States emerged victorious from the Cold War. As Obama liked to say, the obsession with "credibility" should not dictate national security decisions.

In fact, from Saigon 1975 to Berlin 1989, the American Army rebuilt itself successfully, while the Soviets overextended their foreign commitments (especially in Afghanistan). The Reagan administration forced East-West competition in areas where the USSR could not keep up with the West (e.g., arms race). Is a similar situation not foreseeable over the course of the next fifteen years, this time with China playing the role of America's enemy number one?

International politics do not rely on emotion.

Of course this is not impossible. However, we must assess the scope of the defeat that the West has just suffered in Kabul. To draw up a "post-mortem" assessment of the situation, three observations are necessary.

First of all, the global balance of power in the world now appears to be much less favorable to the United States than it was when Saigon fell.

Albeit deeply wounded by the Vietnamese failure, the US at the time remained an unrivaled superpower. The USSR - its great adversary at the time - was already on shaky ground. Its junior partner was a still weak China. The rift between the two had begun, encouraged by the skillful diplomacy of Nixon and Kissinger. However, China is now a rising competitor for the United States, challenging the US for economic and technological supremacy. Russia is proving a solid Chinese ally for the time being, and remains itself a formidable adversary for Washington in certain respects (powerful weapons, cyber security, geopolitical ambitions). American leaders should keep this in mind when they consider showing signs of weakness.

Secondly, the current US withdrawal from Afghanistan is the result of a hasty and vaguely justified decision, and is being executed in a particularly incompetent manner.

This itself is a sign of weakness. On the one hand, the American presence in Afghanistan had been reduced over the years to a "light footprint", dear to strategists (2,500 troops). Commentators claim that the mission of US and NATO forces was too vague and lacked a defined strategic purpose. In fact, it has become apparent that for a relatively modest cost, Western intervention made it possible to prevent the country from slipping into the hands of their enemies. The Taliban will now have to be begged not to give sanctuary to Al Qaeda, or to other terrorist groups.

Of course, the American public wants external interventions to end. However, this is a far cry from the existential crisis America experienced during the Vietnam War - and because Western involvement in Afghanistan had decreased in volume, casualties had been low for several months.

Is Afghanistan proving the illusory nature of "state building" endeavors?

Is Afghanistan proving the illusory nature of "state building" endeavors? The international community has failed to establish a strong or even functional state; although, at least in cities, society has begun to appreciate some of our values, including in terms of women’s rights, which are also increasingly valued in our own societies.

On the other hand, this demonstration of incompetence by Americans in their withdrawal operation is enough in itself to harm their credibility. The intelligence services' forecasts have proven to be particularly unreliable. It is almost unbelievable that American decision-makers did not arrange a fallback base - at Bagram or elsewhere - allowing their armed forces to keep a certain control of events in the case that things did not go according to plan. In other words: it would have been one thing for a major country to decide to end an operation in an orderly and responsible manner; it is quite another to offer this spectacle of a stampede debacle in full view of the rest of the world.

Thirdly, this now creates a perception detrimental to the strategy which the Biden administration had begun to construct - with initial success - to be up to the challenge of competition with China and Russia.

An important aspect of this strategy resides in the consolidation of American alliances, both in Asia and in Europe, with the aim of bridging the two networks of allies. It relies on the assumption that American security guarantees are sufficient in the Indo-Pacific to counterbalance Chinese pressure, and that American power in Europe maintains sufficient credibility to encourage Europeans to contribute to containing Chinese influence. With America's display of weakness in Afghanistan, the fear of a Chinese attack on Taiwan in the next few years has increased by 20 to 30 percent, and the credibility of the US guarantee to some of China's neighbors has similarly waned. In Europe, serious doubts are growing about American interest in supporting peripheral countries - such as Ukraine, for example, or even the Baltic States.

This appalling episode should push Europeans to forge their own vision.

But above all, Biden has acted with a casualness worthy of Donald Trump towards his NATO allies in Afghanistan, the British and Germans in particular. American unilateralism hardly encourages their closest allies to take on new risks alongside America.

Strategists may object to this, claiming that Afghanistan was only a secondary issue for the United States; while areas with high stakes for America would still give rise to resolute American action. One could fear that these differentiations might escape the attention of policy-makers, or at the very least that the signal of weakness sent by the US in August 2021 will incite adversaries to test Washington's real determination, or tempt them to try their luck with a bold move. In the current state of the balance of power, the American withdrawal from Afghanistan might end up having the same effect as Obama's decision in August 2013 not to intervene in Syria - that of encouraging America's rivals to take their chances.

In the short term, Joe Biden's decision for Afghanistan - and the manner in which it was implemented - casts an arguably long-lasting shadow on the Democratic administration's ability to carry out its strategy of competing with China and Russia. However, we should not lose sight of the fact that the United States and its allies still have enough resources to devise a post-defeat strategy in Afghanistan, aimed, among other things, at dissuading the Taliban from turning their country into a terrorist foothold. Moreover, they will likely continue to support the seeds of progress in Afghan society in other ways. Finally, this appalling episode should push Europeans to forge their own vision, which has never been the case when it comes to Afghanistan. The European vision should avoid an "all military" approach and also refrain from oscillating from one extreme to another in terms of external interventions.

Copyright : Wakil KOHSAR / AFP